What was the first thing you did when you woke up this morning? Brush your teeth? Shower? Use the toilet? Most likely you were able to perform one or all of these activities from the comfort of your home. In the developed world household taps are ubiquitous; reliable access to safe water is expected. However, this is not a universal reality. Today, nearly one billion people on the planet live without proximate access to safe water.

That the world’s water resources are unequally distributed is a well-known fact. But what exactly does this mean? What are the implications for the individuals who live without a tap or toilet? In the development community such issues are often viewed through a macro lens, rendering human faces and individual experiences out of focus.

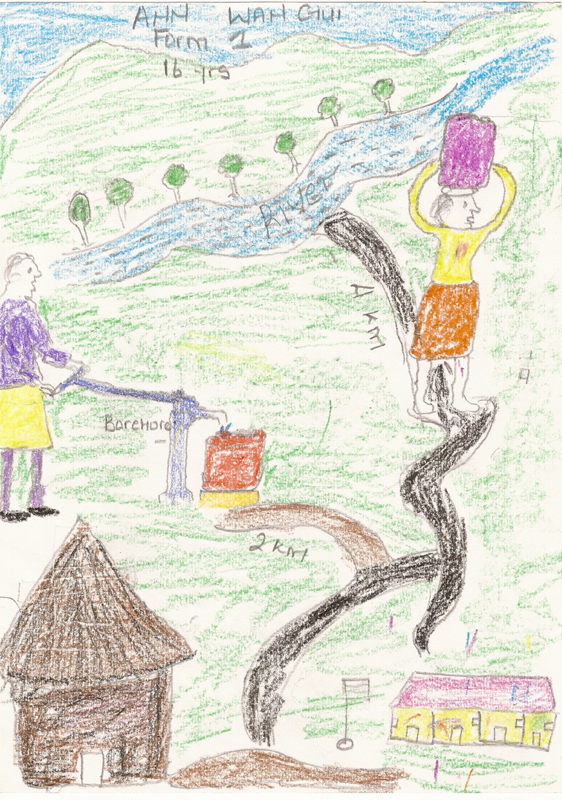

So, let me make this personal. Meet Ann. Several months ago I had the pleasure of meeting Ann while on a research trip to Kenya’s Rift Valley province. Ann, a 16-year-old student at Mwituria Secondary School, is one of the 17 million Kenyans living without a reliable source of safe water.

For Ann, the eldest of four siblings, each day begins before dawn to collect water for her family. Since she was a young girl, Ann has made the four-kilometer walk to fill a jerry can at her community’s only water source – a stream. Ann carries the 20-liter can, weighing 40 pounds, atop her head as she navigates the occasional goatherds and morning foot traffic on the four-kilometer walk home. The trip takes Ann two hours. Once home, Ann promptly rinses, dresses and then sets off on the two-kilometer walk to school with her brothers – that is if she had enough water to wash her school uniform the evening before.

Ann’s story is not uncommon. It is a story shared by millions of women and girls. According to the UNICEF/WHO Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, in a single day, women spend 200 million work hours collecting water for their household. The result: lost productivity, hindered educational development of school-aged girls and persisting gender disparities.

In a recent study I conducted in Laikipia, Kenya on the educational impact of water collection, I found that the lack of access to potable water disproportionately affects the enrollment and retention of female students, especially as you move up the educational ladder. Because women and girls are predominantly responsible for securing their household’s noneconomic resources, they face unequal access to quality education.

However, water collection is only part of a larger picture. Poor infrastructure, such as the absence of girl-friendly sanitation facilities, and the shortage of affordable sanitary supplies also contribute to the persisting gender imbalance in Kenyan secondary schools. Further research on this issue has shown that upwards of 800,000 girls in Kenya miss a week of school per month due to inadequate sanitation facilities and the lack of sanitary supplies.

While significant strides have been made in recent years with regard to women’s rights and universal access to primary education, deeply entrenched social structures and economic volatility have resulted in slow and erratic progress. Today, one in four children in sub-Saharan Africa are not in school – amounting to 45 percent of the global out-of-school population. The majority of these children are girls who, like Ann, live in an environment where traditional social roles prioritize activities such as water collection over academics; marriage over graduation; child rearing over professional pursuit.

The trend is changing, but change comes slowly without the necessary resources.

Presently there is a need within the development community to realign policy and investment decisions with peoples’ immediate needs; in this case water infrastructure and affordable sanitary products. In order to create meaningful and measurable impact, it is necessary to design a range of solutions that are systemic and sustainable. For example, while providing scholarships to girls is undoubtedly an effective method to advance gender parity in education (in terms of enrollment of males and females), without securing access to basic resources such as household water and sanitary supplies, parity does not translate into equality.

Women’s empowerment campaigns such as the Girl Effect, 10×10 and International Women’s Day have been enormously successful in garnering widespread interest in issues of gender inequality in access to resources and power, however, the rising groundswell of concern must now be harnessed to drive substantive change.

Stories like Ann’s give us a better understanding of the interconnectivity of challenges facing humanity. Today’s world is one of stark contrast: one in nine people live without access to safe water and adequate sanitation, yet one in seven people is an active Facebook user; half of India’s 1.2 billion people have mobile phones but lack household toilets; humans have walked on the moon and put robotic rovers on Mars, yet sanitary napkins remain out of reach for millions of women and girls. These realities are opportunities for solutions.

Post by Jenny Emick

Wow! After all I got a blog from where I be capable of truly take useful information regarding my study and knowledge.